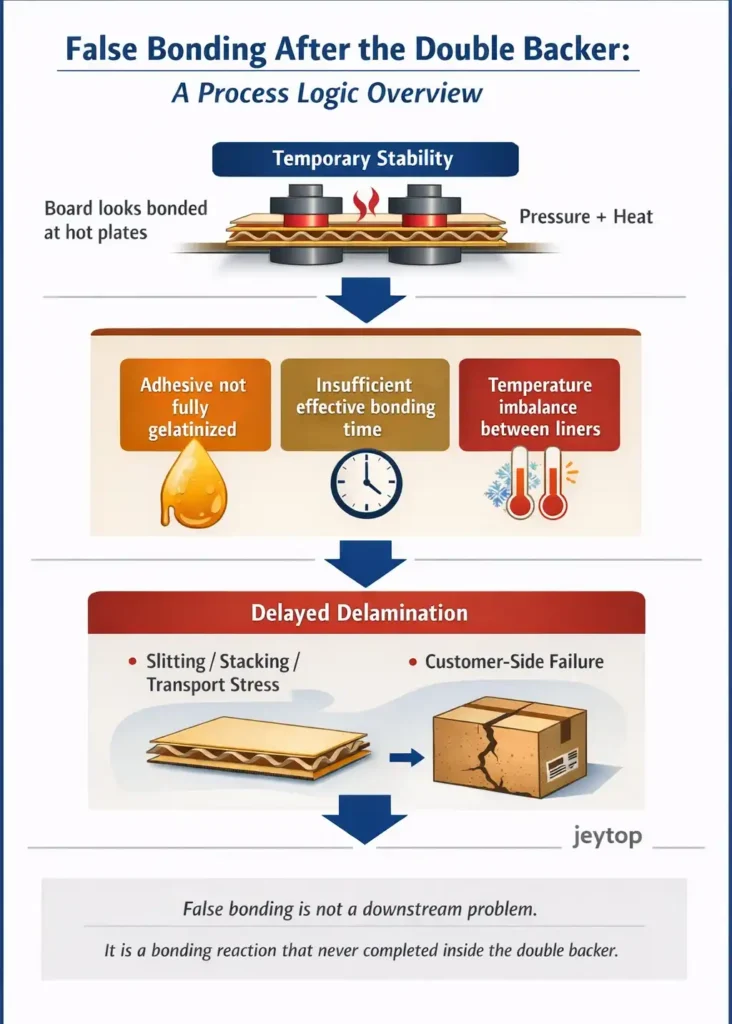

Core purpose: Help you identify the most deceptive post–double backer bonding failure — false bonding — and prevent delayed delamination from exploding later at the customer site due to wrong on-line decisions.

Conclusion First (for those under pressure)

If your board looks perfectly fine as it leaves the double backer, but starts to delaminate during slitting, stacking, or even after delivery to the customer, the problem did not appear suddenly.

The core misjudgment:

“Nothing is delaminating on the line = the problem is solved.”

The harsh reality:

Heat and pressure may only be temporarily masking a bonding failure.

This is a delayed failure, and its damage is often far greater than delamination that shows up immediately on the machine.

What Is “False Bonding” After the Double Backer?

Forget textbook definitions. On the shop floor, false bonding speaks its own language.

Typical symptom:

The board exits the hot plates looking flat and tight. It even feels solid when pressed by hand.

But once it experiences longitudinal or transverse cutting stress, stacking pressure, or transportation vibration, the bond suddenly separates — without warning.

The technical reality:

False bonding is not “weak bonding.”

It means the bonding reaction never actually completed.

The adhesive was dried into a solid film or powder, instead of forming a true fiber-to-fiber bond with the paper.

(In corrugator operations, this failure mode is commonly referred to as false bonding after the double backer.)

Key signal to remember:

Any delamination that appears after the board leaves the heat-and-pressure zone should be treated first as suspected false bonding.

Why “It Looks Fine” Is the Most Dangerous Signal

“It looks okay” is the most dangerous phrase in this scenario, for three reasons:

- It lowers your guard

Because the defect does not show up immediately, it is easily misclassified as a random event or a downstream issue — and the best intervention window is missed. - It pushes you into wrong decisions

Based on appearance alone, you may increase speed, release questionable production, or blame later processes — all of which allow the real problem to grow. - It magnifies damage at the final stage

When delamination finally appears at the customer, the cost of tracing and recovery is often tens of times higher than handling it correctly on the line.

In short:

You are being misled by temporary calm at the end of the line, while the real cause was already planted upstream.

Check These Three Points First — In This Exact Order

When false bonding is suspected, follow this sequence strictly. Do not skip steps.

1. Is the paper temperature balanced before bonding?

Why it matters:

If liner and singleface enter the double backer with a large temperature difference, the colder side acts like a heat sink, stealing the energy required for adhesive gelatinization. The bonding reaction on that side never fully completes.

Quick check:

After the preheaters and before the double backer, carefully feel both sides of the paper for noticeable temperature differences.

For accuracy, compare both sides with an infrared thermometer.

2. Effective bonding time vs. line speed

Why it matters:

Starch adhesives require time, not just a temperature peak, to gelatinize.

Increasing line speed shortens effective dwell time in the hot-pressure zone, leaving the adhesive only partially reacted.

Critical understanding:

Speed can never fix a bonding problem.

It only masks or worsens it.

If increasing speed ever seemed to “solve” delamination, that is often a textbook case of false bonding — the failure was simply postponed.

Related reminder:

This follows the same logic as our previous article: for single-side delamination, don’t touch speed first. Speed is a result, not a root cause.

3. Is adhesive gelatinization synchronized with the hot-plate temperature profile?

Why it matters:

This is the most subtle factor.

Every adhesive has a specific gelatinization temperature range. If the hot-plate temperature profile is misaligned — for example, too cool in the front and too hot at the back — the adhesive may still be ungelled in the optimal pressure zone, or over-dried before leaving the plates.

(Industry-standard technical resources — including TAPPI’s Technical Information Papers on corrugating adhesives and starch gelatinization — explain why sufficient heat and effective bonding time are essential to proper bond formation.

🔗 https://www.tappi.org/publications-standards/standards-methods/numerical-index-for-technical-information-papers-tips/)

Common blind spot:

Many operators focus only on peak temperature, ignoring the time–temperature relationship.

The adhesive must stay within a suitable temperature window long enough to complete the reaction.

Three Things You Must Not Do First

Before completing the checks above, these actions will only hide the truth and make diagnosis harder:

- Do not immediately change line speed (up or down).

Speed directly alters the only constant factor — time — and disrupts your ability to judge the process, making false bonding even more unpredictable. - Do not blindly increase adhesive application.

More adhesive requires more heat and more time. Without knowing the root cause, this only worsens the energy imbalance. - Do not instantly blame paper quality.

Paper is one factor, but concluding “bad paper” before completing a systematic check shuts down all meaningful process correction and does not help solve the current run.

A Simple Engineering Reality Check

Shift your diagnostic viewpoint upstream.

If delamination occurs after the board leaves heat and pressure, the problem is not in the slitter, stacker, or truck.

It exists earlier — within the double backer’s thermal and pressure process — and it should have been measurable and detectable there.

This is exactly why false bonding after the double backer so often goes unnoticed until delamination appears downstream.

Your job is not to wait for failure to explode at the final stage, but to identify it while it is still being masked, using the right sequence and the right tools.

That is what real preventive quality control looks like on a corrugator line.