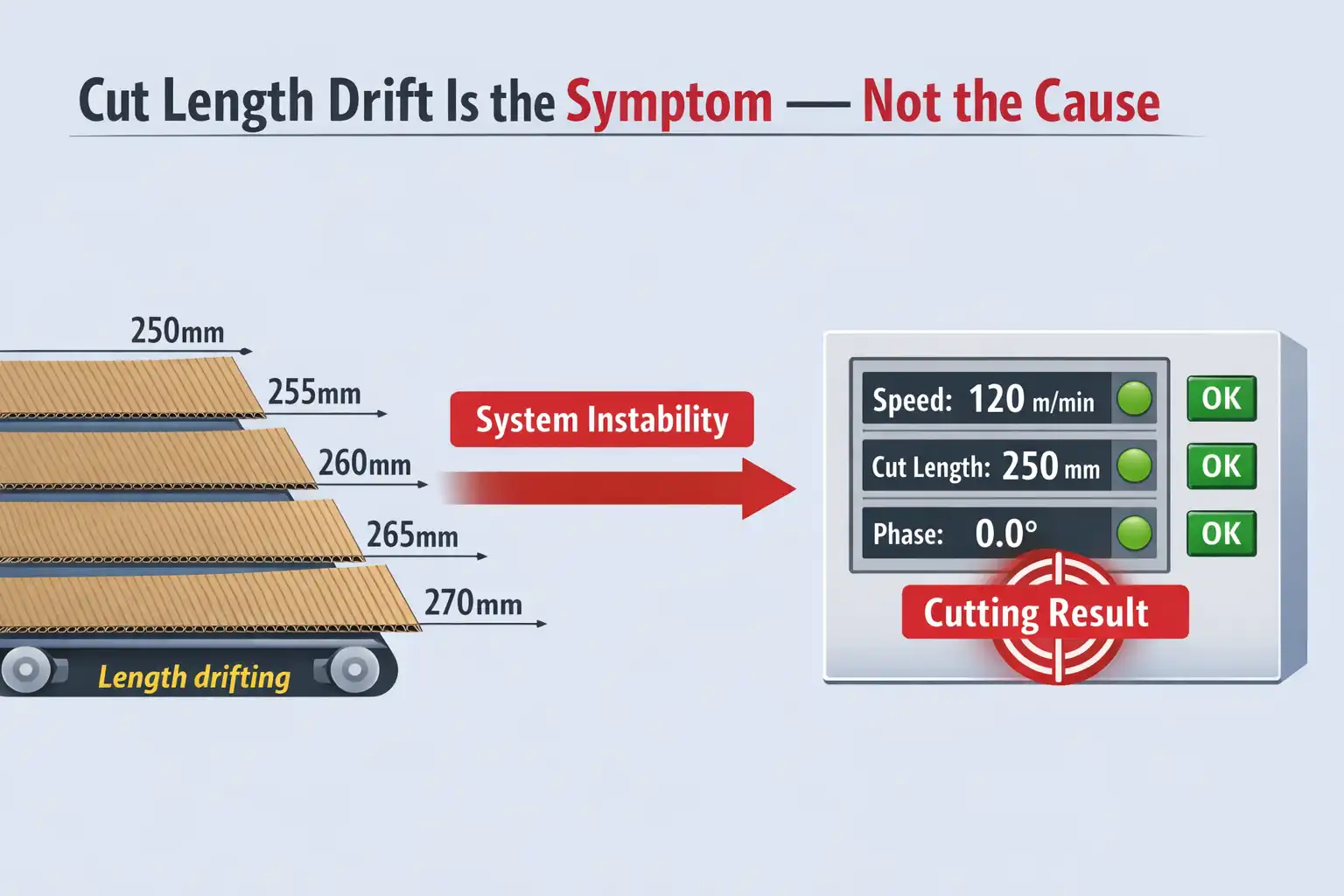

When cut length starts drifting without warning, while all control panel settings — length, speed, phase — remain unchanged, stop your hand before touching the cut-length parameter.

At this moment, one critical understanding must be established immediately:

Cut length drift is rarely caused by the cutting section “cutting wrong.”

It is far more often the first and most honest signal that overall line stability has cracked — and the cutting section is simply the first to report it.

This article does not teach you how to “adjust the length back.”

It answers a far more urgent operational question:

At the moment cut length begins to drift,

which section of the corrugator should be stopped first

to minimize loss and preserve diagnostic evidence?

Minute One: Identify Who Is Actually Drifting

Before taking any action, use one minute to answer this core question:

Is the cutting section generating the error —

or is upstream instability already present, with the cutter faithfully executing a wrong rhythm?

Quickly observe three things.

1. What does the drift look like?

- Continuous, smooth drift in one direction

→ Strongly suggests a systemic, cumulative error. - Sudden jumps, oscillation, poor repeatability

→ More likely a synchronization, transmission, or response fault.

2. Does the drift synchronize with other changes?

- Does it appear together with subtle speed fluctuations?

- Is it accompanied by visible tension changes — flutter, slack, or uneven board spacing?

3. What does the cut edge look like?

- Clean, sharp edges with unstable length

→ The problem is very likely upstream. - Frayed, torn, or rough edges

→ The cutting section itself may be directly involved.

Fast conclusion:

If you see continuous drift + clean cut quality, suspect upstream first — not the cutter.

Minute Two: A Non-Negotiable Rule

Never Stop the Cutting Section First

This is the most important correction this article makes:

The cutting section is almost never the creator of length error —

it is the final amplifier of upstream instability.

Why stopping the cutter first is dangerous:

- The cutter is a strict executor.

It cuts exactly where the board is at the command moment — nothing more. - It is also a perfect mirror.

It cannot correct upstream position or speed errors; it only converts them into precise length deviation.

If you stop the cutting section first:

- You freeze the result while allowing the cause to continue.

- You destroy time correlation, making root-cause diagnosis far harder after restart.

- You risk secondary faults — accumulation, congestion, or tension shock.

Build this mental model firmly:

Length is not created by the cutter.

It is fed to the cutter by upstream rhythm.

Minute Three: Where You Should Stop First

Correct stop decisions follow one rule:

Trace the error upstream.

Stop where the error is being generated — not where it is being displayed.

Follow this priority order.

First Priority: Tension and Conveying Stability Loss

Typical signals:

- Displayed speed remains constant, but board spacing visibly changes.

- Pre-cutter conveying rhythm becomes uneven.

- Boards show subtle forward-back “creep” before entering the cutter.

Core logic:

Length drift is a time-position error.

The most common root cause of time error is unstable tension or conveying synchronization.

Second Priority: Dryer–Cutter Rhythm Lock Failure

Typical signals:

- Length setpoint is correct.

- Actual cut position drifts progressively forward or backward.

- Drift accumulates over time.

Core logic:

Modern cutting does not measure length physically —

it cuts at a time-synchronized trigger point tied to line speed.

If that time reference drifts, length error is mathematically unavoidable.

Third Priority (Last): Cutter Synchronization Reference Itself

Only consider this when evidence is clear:

- Repeated commands produce inconsistent knife positions.

- After excluding upstream factors, cut length becomes random.

- Length drift and cut quality deteriorate simultaneously.

Only then should you investigate encoder feedback, servo response, or mechanical coupling.

Minute Four: Three Instinctive Reactions That Must Be Prohibited

❌ Immediately adjusting the cut length parameter

→ You mask process error by modifying the result, losing the only true reference.

❌ Changing line speed repeatedly “to feel it out”

→ Speed is the system’s heartbeat. Changing it disturbs heat, glue, tension, and synchronization at once.

❌ Continuing to run while compensating under complaint pressure

→ Chasing results under stress is how small instability becomes systemic failure.

Minute Five: The Only Output That Matters

After five minutes, you do not need any new parameter values.

You must deliver a decision-level conclusion:

- “Current length drift originates from unstable line synchronization/tension, with the cutter passively amplifying the error.”

Or, only with strong evidence:

- “Current drift is confirmed to originate from cutter synchronization reference loss.”

That conclusion determines everything next:

- Controlled continuation or immediate full stop?

- On-site correction or escalation to system-level investigation?

Final Reminder

Cut length drift is never the cutter “cutting the wrong place.”

It is the production system stating — with absolute precision:

Our previously matched operating rhythm has shifted.

Mature cutting management is not defined by how fast length is adjusted after deviation —

but by this capability:

When the first out-of-spec board appears,

can you stop the section creating the error —

instead of the section reporting it?