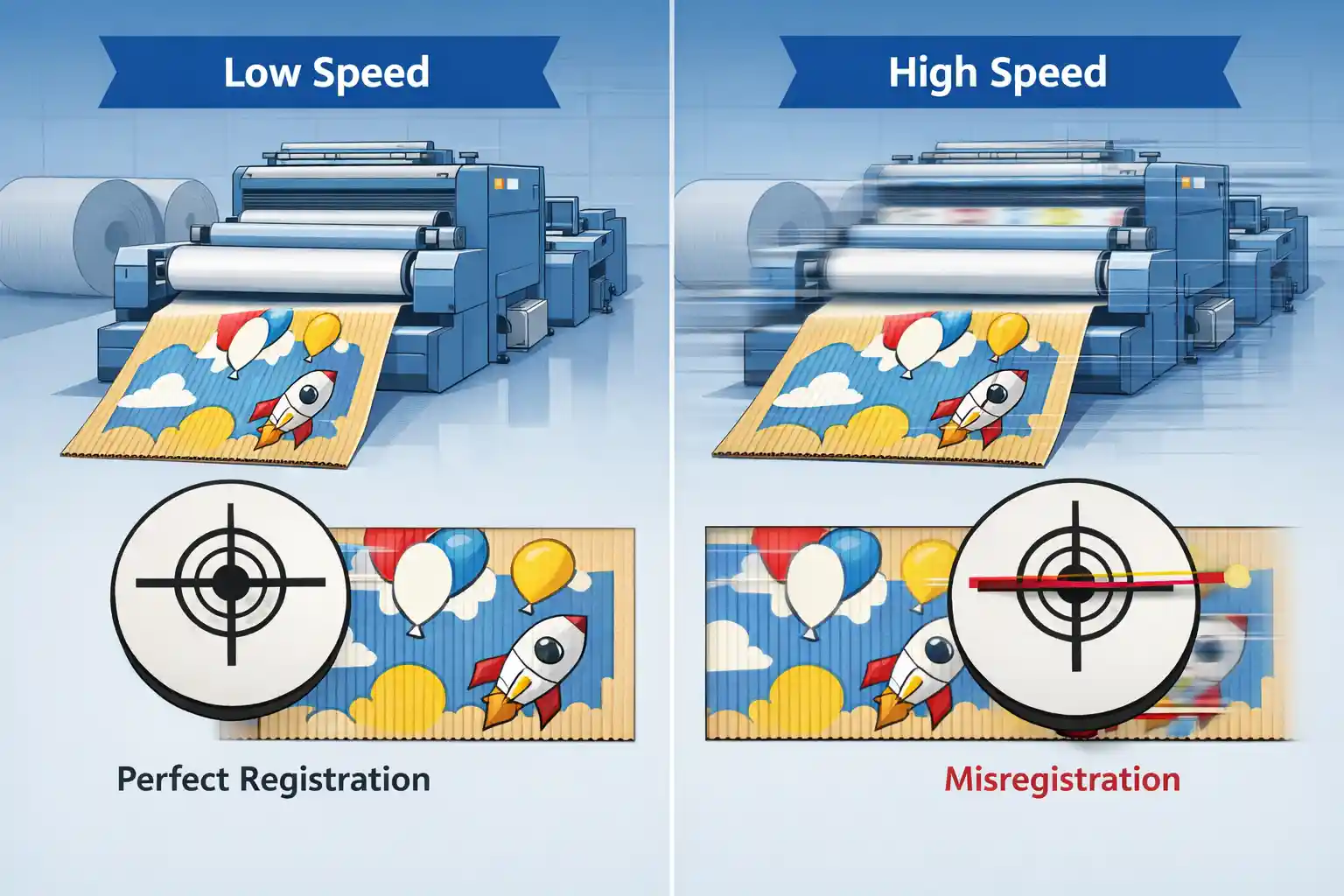

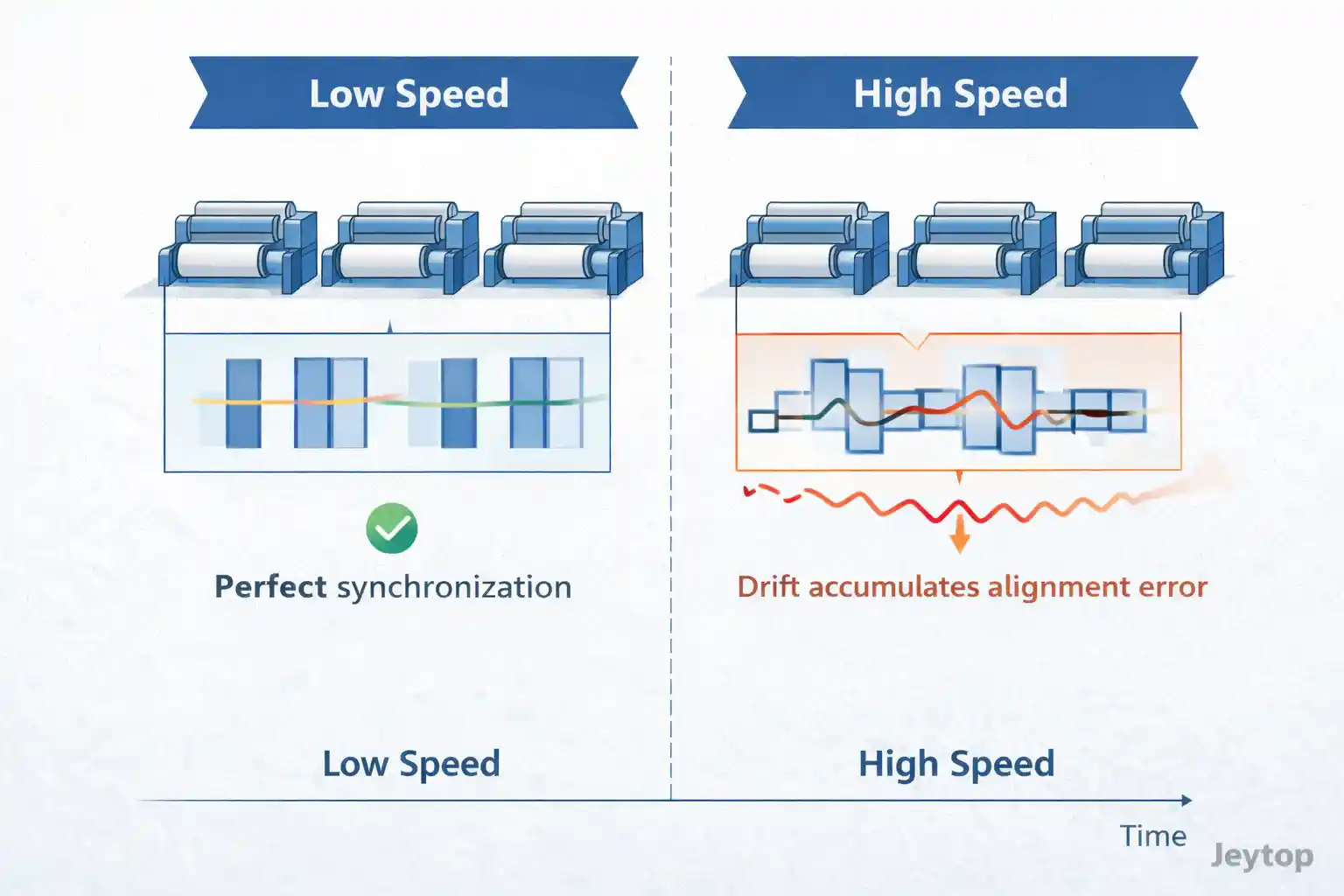

When a printing line runs slowly, registration is stable and predictable.

Increase the speed, and the problem starts quietly: registration drifts, certain color units begin to lag, and waste gradually accumulates.

The instinctive reaction on the shop floor is almost always the same:

“Let’s tweak the registration parameters again.”

This is exactly where the most expensive mistakes begin.

At high speed, every incorrect adjustment amplifies scrap, hides the real fault, and pushes the system closer to irreversible loss.

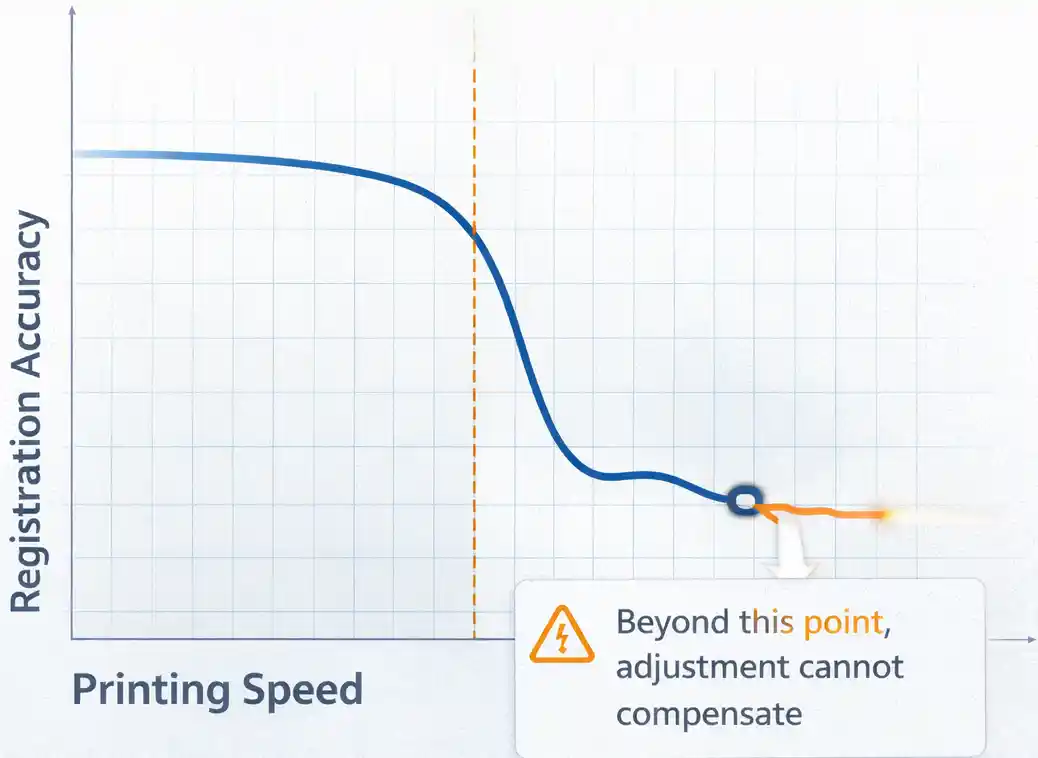

When registration deteriorates after a speed increase, the issue is rarely how to adjust — it is whether the system has crossed its operating boundary.

This article is not about fine-tuning registration.

It is designed to help you determine, within minutes, whether your line should keep running, slow down, or stop — before misjudgment turns a controllable deviation into a full-order failure.

A critical principle: suspect the system before blaming the operator

In modern flexographic printing systems used for corrugated packaging, stability at low speed but instability at high speed almost never points to operator error.

Speed acts as a stress test.

When velocity increases, mechanical vibration, signal latency, material behavior, and control response are all amplified.

Registration deviation is not a random fault — it is the system warning you that execution is no longer keeping pace with command.

Misregistration ≠ wrong parameters

Misregistration = system synchronization under pressure

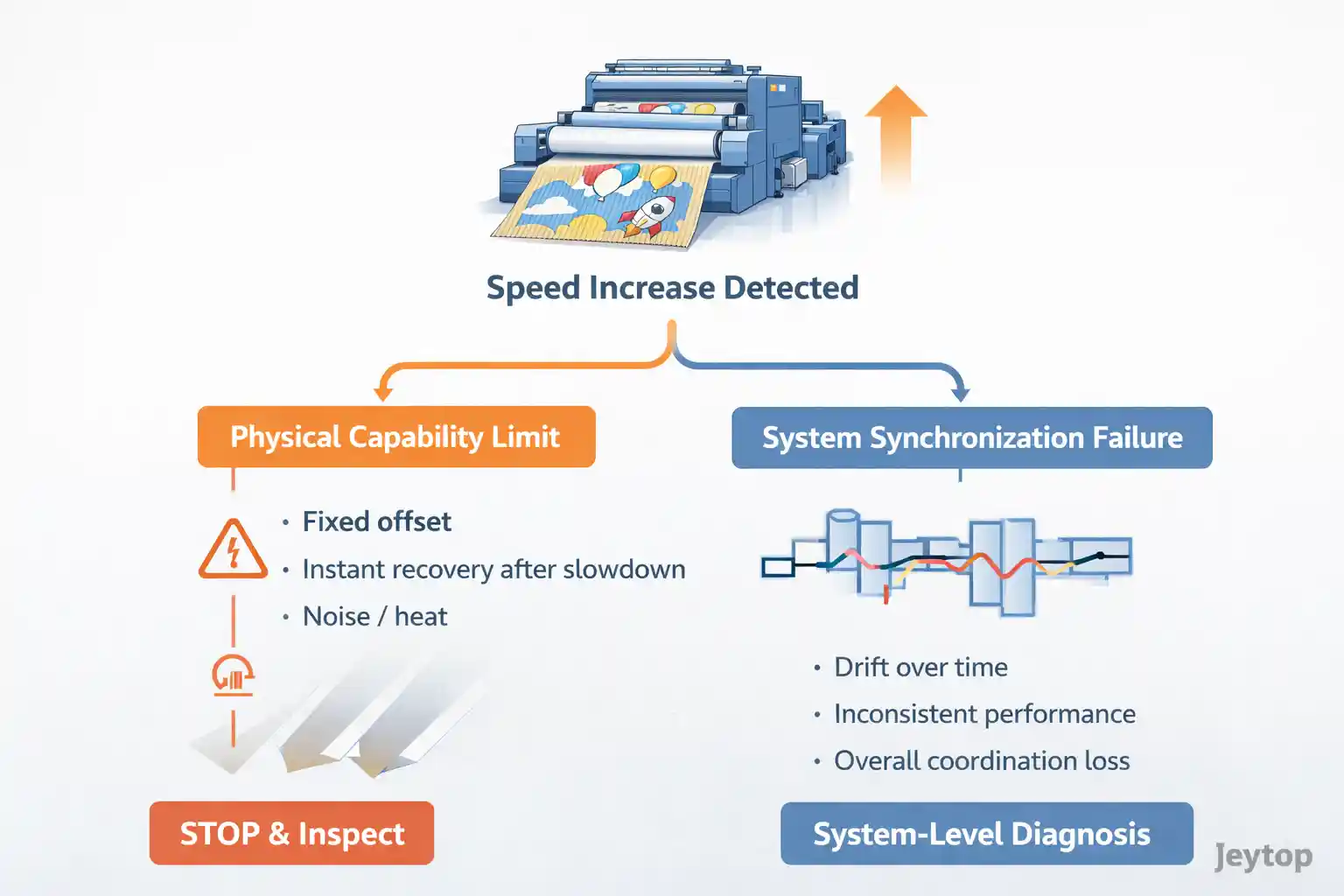

The first and most important decision: boundary limit or synchronization failure?

Standing at the machine, you must answer one question before taking any action:

Is this a hard physical limit, or is the system losing coordination?

Scenario A: the physical capability limit has been exceeded

This is a hardware boundary issue and requires immediate caution.

Typical visible signals:

- At a specific speed threshold, one color unit suddenly shows large misregistration; reducing speed restores accuracy immediately

- Registration deviation is consistent and directional (e.g., always drifting to the same side)

- Physical symptoms appear: abnormal noise, localized overheating of motors or bearings, or a unit that can never “catch up” no matter how it is adjusted

Quick verification (no instruments required):

Run the line at a stable mid-speed for 5–10 minutes.

If misregistration begins to accumulate in a predictable pattern, the system is already at or beyond its mechanical limit.

Conclusion:

This is not an optimization problem — it is a capability problem. Continuing to push speed risks structural damage, not just scrap.

Scenario B: system synchronization is breaking down

This is the most common — and most misdiagnosed — situation.

Typical on-site symptoms:

- Registration does not collapse instantly, but drifts gradually over time

- The same job runs well in the morning and poorly later in the shift

- Each unit appears “acceptable” on its own, yet overall alignment deteriorates

- The effect feels like loss of rhythm rather than a single fault — like a team walking in step without a clear cadence

Conclusion:

This is a system-level coordination failure, not an isolated component issue.

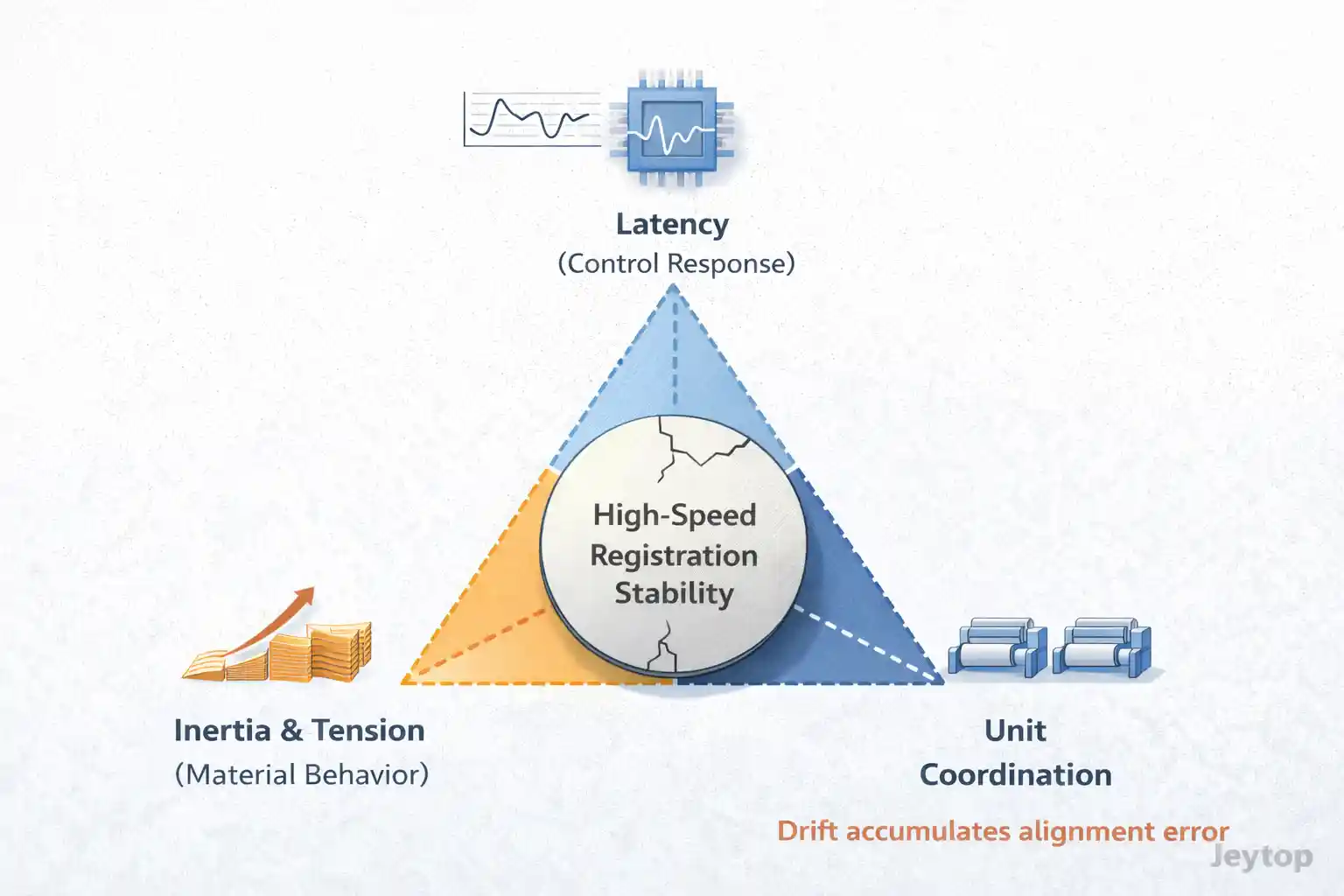

What really determines high-speed registration stability

Once synchronization failure is suspected, stop chasing registration parameters and examine the underlying variables that actually govern performance.

1. Control latency and response timing

At low speed, milliseconds of delay are invisible.

At high speed, the same delay translates into measurable positional error.

If control algorithms, servo response bandwidth, or signal integrity cannot keep pace, commands arrive on time — but execution does not.

2. Energy balance and material behavior

Increasing speed changes the physical behavior of the board.

Inertia, airflow, tension, and drying dynamics all become nonlinear.

Critical upstream check:

If corrugated fiberboard already contains internal stress, warp, or waviness from upstream production, high speed will magnify these defects beyond correction capability.

(See corrugated board flatness control for upstream diagnostics.)

In such cases, software-level synchronization adjustments are futile.

3. Multi-unit coordination

Modern printing lines are long, interconnected systems.

Small speed variations in early units are amplified downstream.

Each section may appear stable individually, but without unified coordination, cumulative error is inevitable.

Actions that must be avoided before a clear diagnosis

Until the system is clearly categorized, the following actions should be explicitly prohibited:

- Aggressively chasing registration parameters

This masks the real failure mode and delays intervention, often multiplying repair cost. - Continuing high-volume production without direction

Synchronization failures worsen over time; they do not self-correct. - Using increased pressure or slight speed reduction to “force stability”

This builds internal stress and often triggers more severe downstream failures.

High-speed misjudgment converts manageable deviation into systemic loss.

The real difference between equipment suppliers

Higher speeds, narrower tolerances, and lower material weights are unavoidable industry trends.

What separates profitable plants from struggling ones is not who runs fastest — but who understands when not to run.

At Jeytop, integrated manufacturing means delivering not just machines, but predictable operating boundaries.

Our systems are designed with unified mechanical structure, control logic, and synchronization strategy — so capacity limits are known before they are crossed.

Because reliability is not about how fast a line can run,

but whether it can run consistently, knowingly, and without gambling.