Nothing has changed on the control panel.

The anilox rolls, ink type, and even the formulation are exactly the same as they were during hours of stable production.

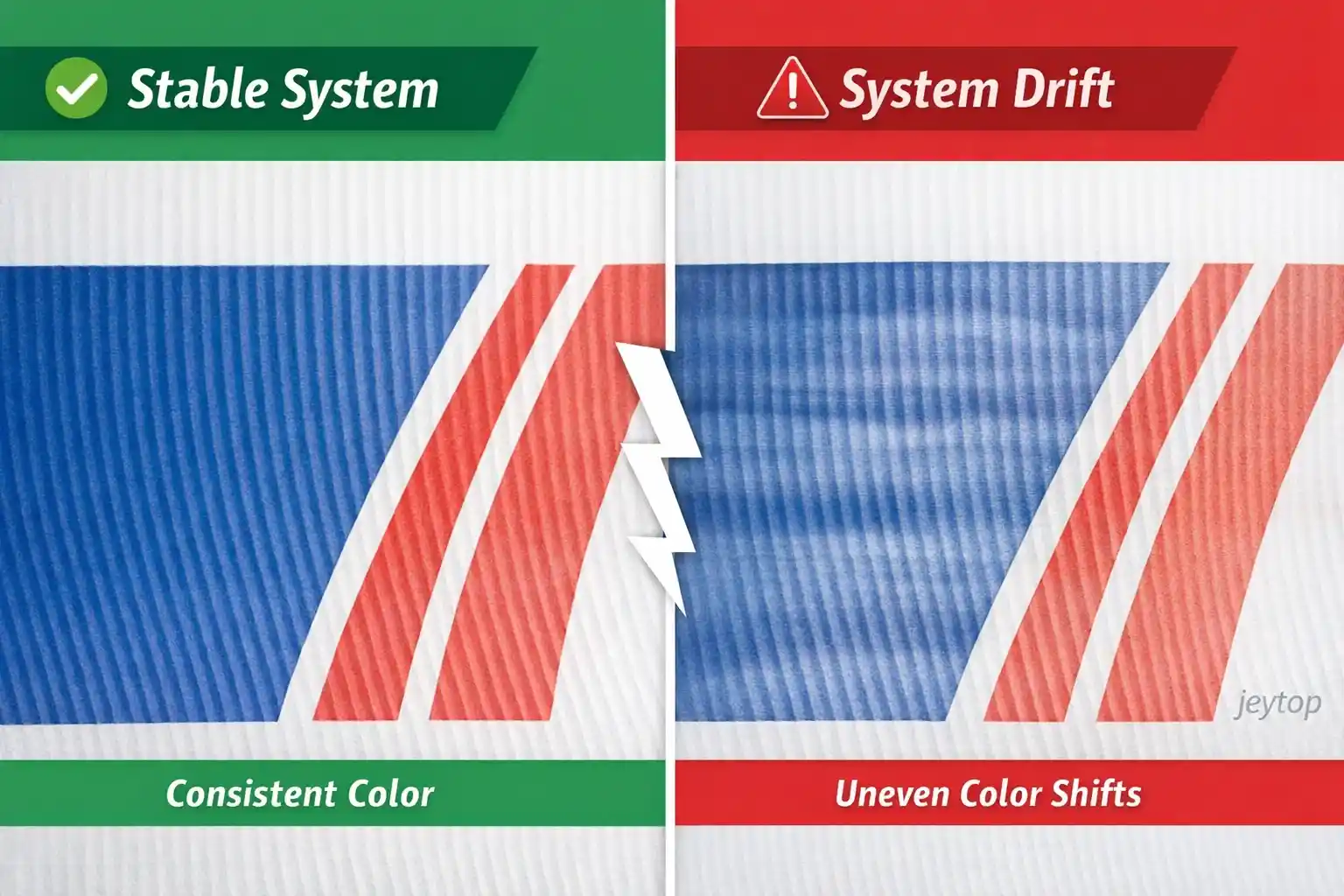

Yet the color starts to drift—lighter, darker, unstable—moving with the rhythm of the machine.

The first reaction on the shop floor is almost always the same:

“Is there something wrong with this batch of ink?”

This instinct is expensive.

On a high-speed printing line, just 10 minutes of trial-and-error color chasing around the ink system can cost thousands of boxes in lost deliverable output. In a modern printing plant, time is the most expensive raw material.

Here is the counterintuitive truth you must accept first:

During continuous production, the probability that ink itself suddenly “goes bad” is far lower than the probability that the printing system has already lost stability.

Color variation is rarely the root cause.

It is usually the first visible alarm of a system drifting out of its stable operating window.

This article is not about how to adjust ink.

It is a 5-minute decision framework to help you determine one critical thing:

👉 Should the line keep running—or should it stop?

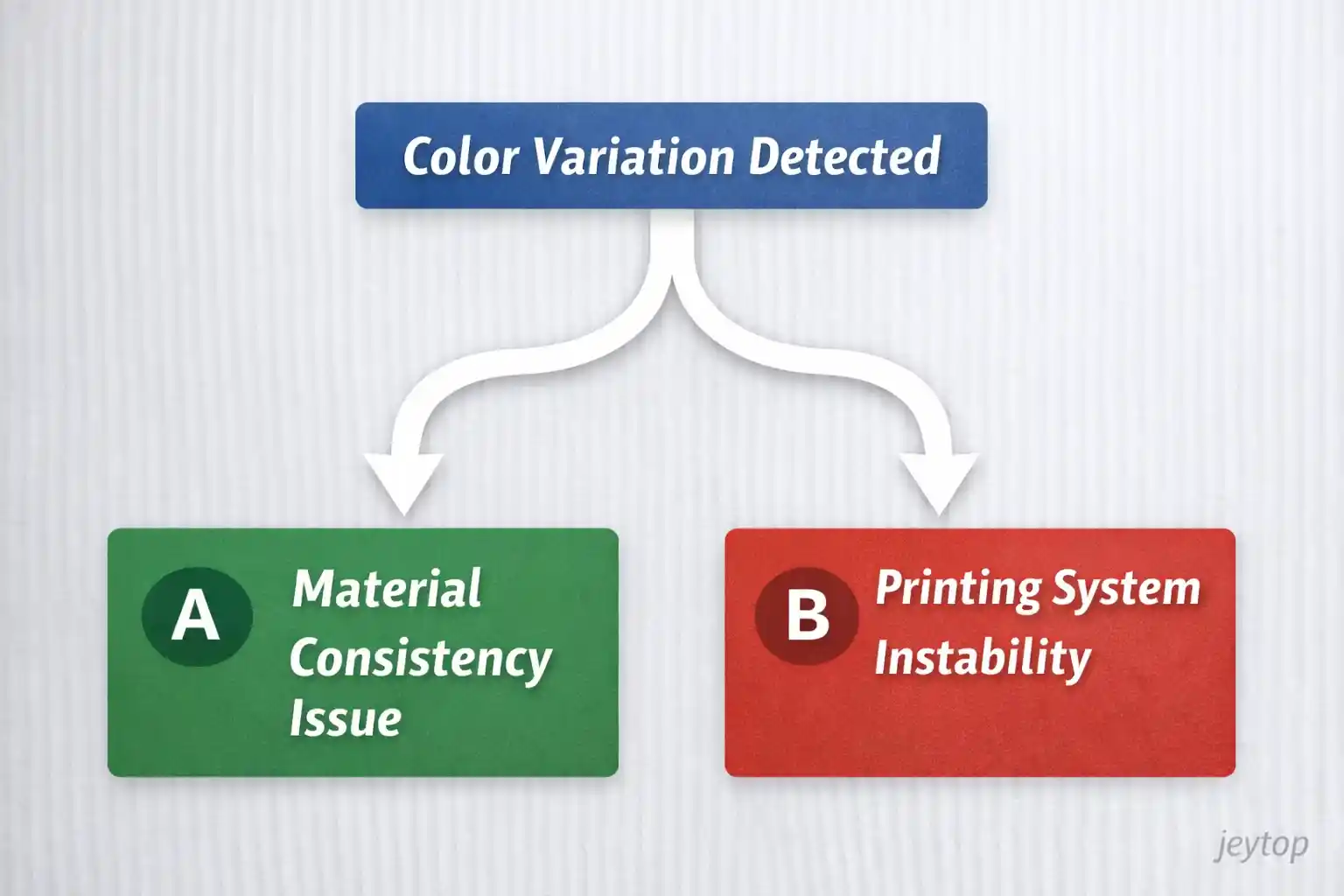

Step 1: Decide the Direction Before Assigning Responsibility

Two Paths — You Must Choose One

Before making any adjustment, you must complete this first diagnosis.

Color variation is a result, not a cause.

It comes from only two fundamentally different directions.

Path A: Material Consistency Has Been Disrupted

(Ink or substrate has changed)

Typical signals include:

- Strong correlation with a specific batch

The problem appears immediately after switching ink or board batches and improves after reverting. - Random, irregular color distribution

Color differences appear scattered, without rhythm, pattern, or repetition. - Ink change provides only temporary relief

The issue disappears briefly after changing ink, then returns.

Critical cross-check (often overlooked):

When suspecting materials, always verify board ink absorption consistency.

Fluctuations in board moisture content can significantly alter fiber absorption rates, visually appearing as uneven color density.

Path B: Printing System Stability Has Been Lost

These signals are fundamentally different:

- Strong correlation with speed

Color variation intensifies as speed increases and improves when slowing down. - Rhythmic or periodic patterns

Repeating banding, stripes, or cyclic density changes are clearly visible. - Progressive deterioration over time

The longer the line runs, the more unstable the print appears.

Core rule:

When color variation shows regularity or synchronization with machine rhythm,

the root cause is almost never the ink—it is the printing system itself.

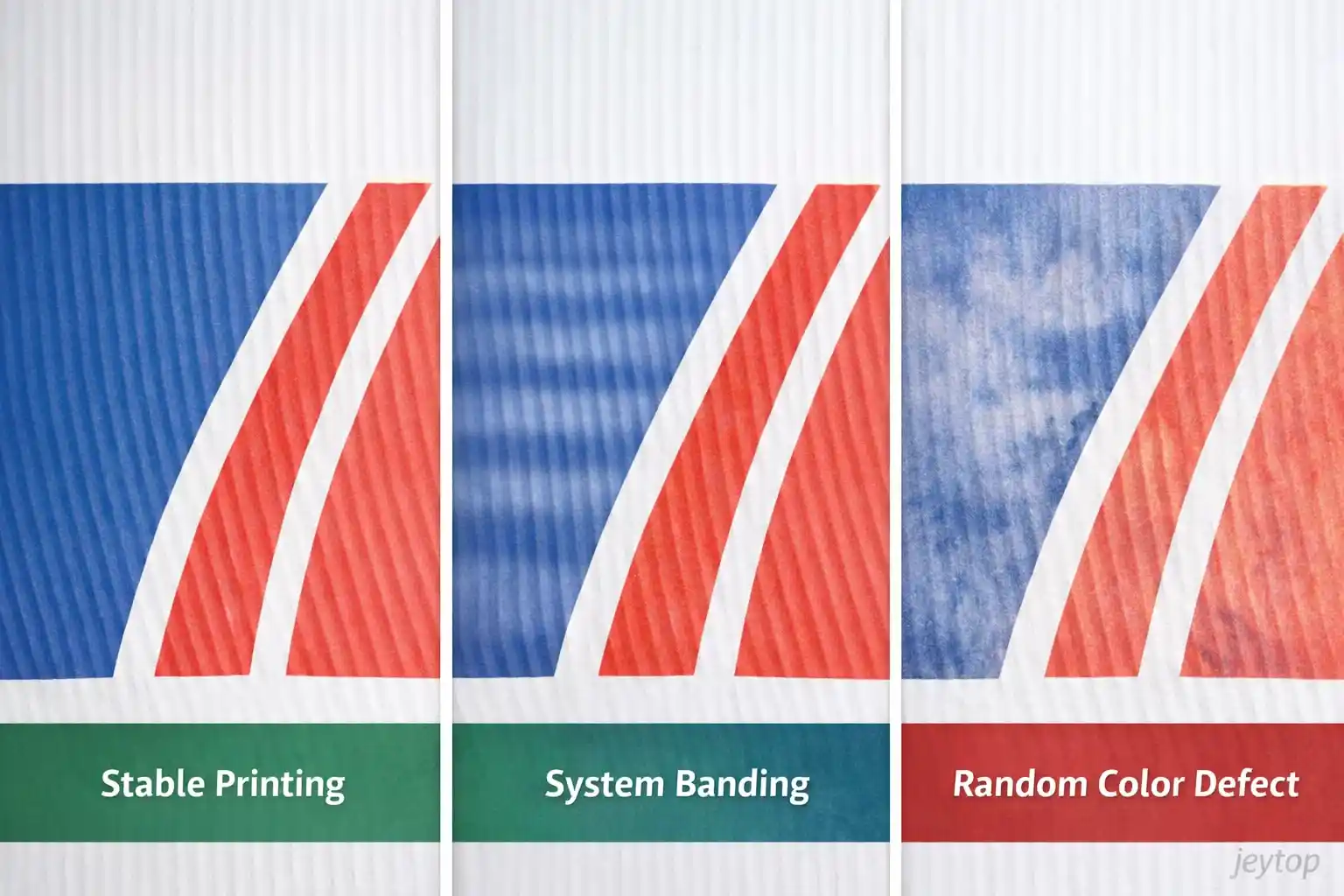

Step 2: Use Visual Evidence to Identify the Root Cause

Compare what you see on your line with these three reference states:

State A — Stable Reference

Uniform color, no visible banding, consistent output over extended runs.

State B — System Instability Evidence

Regular horizontal or circumferential banding.

This typically points to mechanical vibration, drive inconsistency, roll eccentricity, or pressure imbalance.

Regularity itself is proof of a system issue.

State C — Material or Energy Mismatch Evidence

Patchy, cloud-like fading without a clear direction.

Often related to ink transfer interruption, substrate absorption variability, or drying energy mismatch.

Step 3: Why “Chasing Ink” Is the Most Dangerous Reaction

Once the diagnosis points to Path B (system instability), adjusting ink becomes the worst possible move.

Why?

In an unstable printing system, the ink path is the last component affected, yet the first symptom you can see.

The real root cause usually lies upstream in three system-level variables:

- Speed Matching

Has production speed exceeded the stable coordination window of mechanics, drying capacity, and ink transfer? - Energy Distribution

Is drying energy evenly delivered? Local over-drying or under-drying immediately alters visual density. - Unit Synchronization

Are tension, registration, and pressure still aligned across all color units?

A minor drift in one unit is often amplified downstream.

Think of it this way:

Trying to fix color by adjusting ink in an unstable system is like trying to steady a glass of water on a shaking table.

You move the glass—but the table keeps shaking.

Step 4: Three High-Risk Actions That Must Be Prohibited

Before completing the A/B diagnosis, the following reactions must be strictly avoided:

❌ Repeated micro-adjustments to chase color

Result: Ink balance collapses, local defects spread across the sheet, and system behavior becomes uncontrollable.

❌ Continuing high-volume production without clarity

Result: Minor deviations escalate into full-batch rejection within minutes, multiplying losses exponentially.

❌ Increasing pressure or tweaking speed to “force” stability

Result: True mechanical or transmission warnings are masked, often causing irreversible damage to plates or rolls.

These actions may appear effective in high-tolerance environments.

In today’s high-speed, low-margin printing, they usually destroy the entire production window.

Final Judgment:

Color Variation Is a Stress Test of Your Decision Discipline

Modern printing competition is no longer about who knows more ink formulas.

It is about who maintains system stability under pressure.

The factories that outperform others are not those that adjust ink faster,

but those whose teams can make the correct stop-or-run decision within minutes.

Color variation is not a technical failure.

It is a discipline test.

And in printing, protecting system logic means protecting profit.