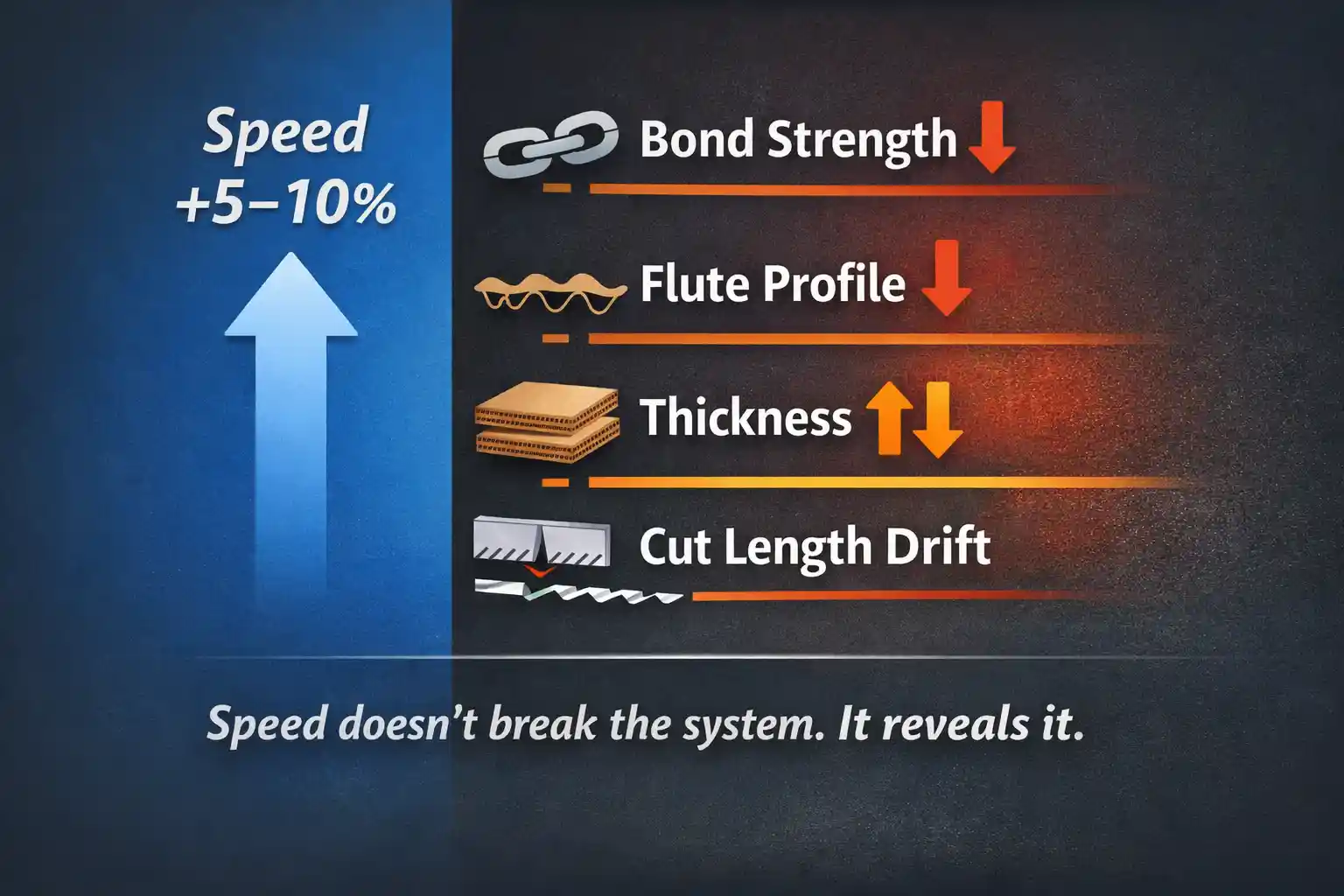

After increasing line speed by 5–10%, the first hour may look acceptable.

Then problems begin to surface—weak bonding, flattened flutes, unstable thickness, drifting cut length.

In most plants, the instinctive reaction is immediate and unanimous:

“The speed is too high. Roll it back.”

Pause before making that call.

Because in many cases, what you are facing is not a simple process failure, but a management-level misjudgment—one that quietly limits the long-term capability of the entire system.

The real question is not whether the line is running “too fast.”

It is this:

Can your production system still maintain all critical process windows under the new rhythm?

This article is not about how to increase speed.

It is about how to decide when rolling back speed is necessary—and when it is the wrong decision.

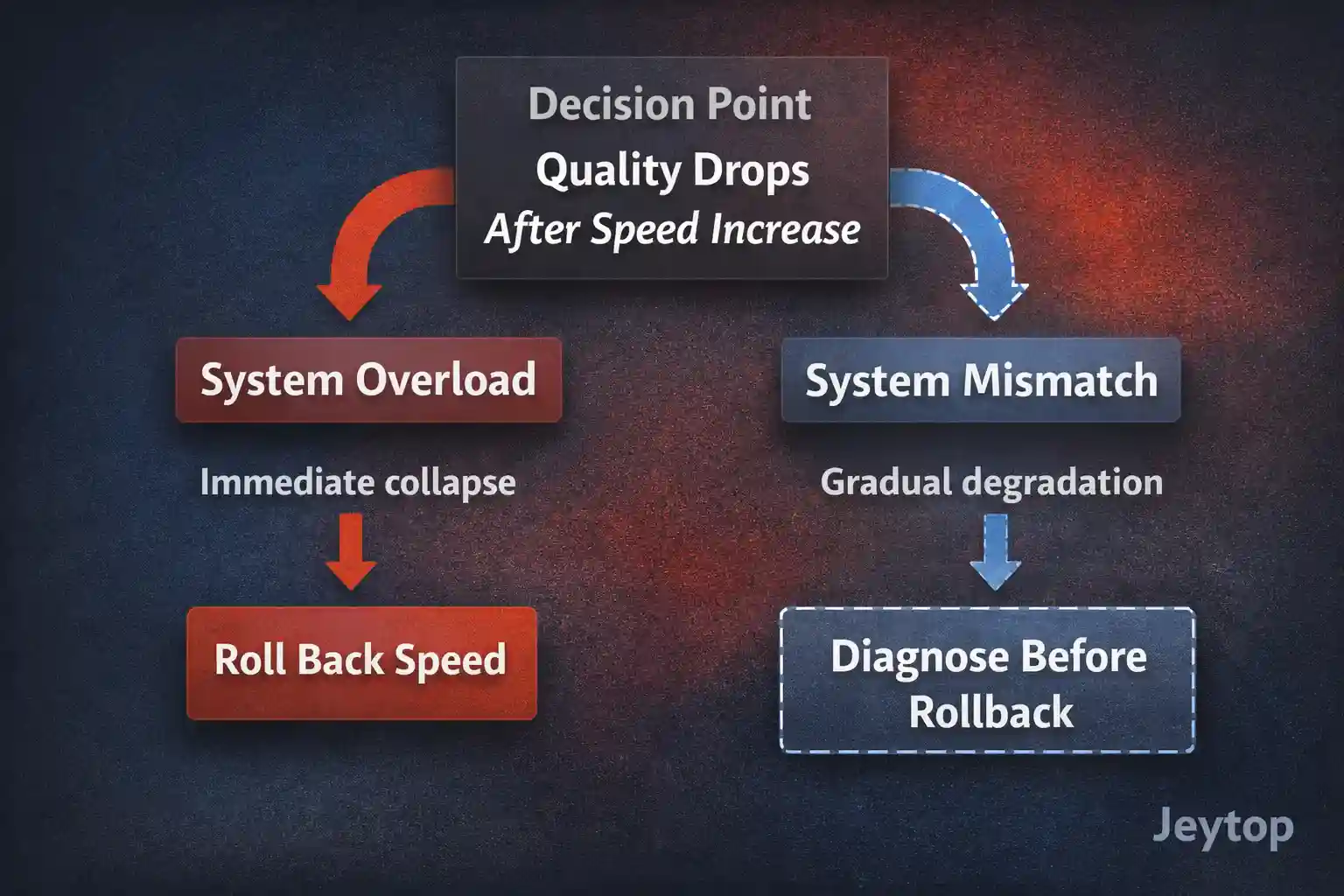

Step One: The Critical Diagnosis — System Overload or System Mismatch?

Before touching any parameter, the situation must be classified into one of two fundamentally different conditions.

1️⃣ System Overload (Speed Must Be Reduced)

Typical signals:

- Quality collapses immediately after the speed increase

- Failures are severe, widespread, and irreversible

- The line physically “cannot keep up”

What this means:

The system has reached a hard physical limit—energy supply, drying capacity, or mechanical strength is insufficient.

Correct decision:

✔ Reduce speed immediately.

This is not retreat; it is respect for physics.

2️⃣ System Mismatch (Speed Should NOT Be Rolled Back Immediately)

Typical signals:

- Quality does not collapse instantly

- Problems appear gradually, worsen over time, and spread across multiple processes

What this means:

The system has potential, but its internal coordination—heat, moisture, tension, timing—has not yet synchronized with the new speed.

Common management mistake:

✖ Rolling back speed too quickly.

This erases critical diagnostic signals and hides the real bottlenecks.

A plant manager’s first responsibility is not to judge speed, but to judge this:

Has the system been pushed beyond its limit—or merely out of rhythm?

Step Two: Three Signals That You Should NOT Roll Back Speed Yet

If the following patterns appear, treat speed rollback as a warning sign—not a solution.

✔ Signal One: Gradual, Cumulative Quality Degradation

- The first 30–60 minutes seem stable

- Bonding weakens, thickness variation grows, flute structure slowly collapses

System logic:

This is not overload.

It is energy, moisture, and pressure drifting out of balance over time under a compressed process window.

✔ Signal Two: Quality Problems Spread Across the Entire Line

- Wet-end forming, drying, cutting, stacking—all begin to degrade

- No single machine stands out as the failure point

System logic:

Isolated problems point to equipment.

Line-wide degradation points to system timing and coordination failure.

✔ Signal Three: Operating Margin Disappears

- Production continues, but barely

- Small adjustments cause violent fluctuations

- Operators feel they are “walking on a knife edge”

System logic:

The system has slid from the center of its stable operating window to its edge.

The problem is not speed itself—it is loss of robustness.

Step Three: Why Rolling Back Speed Is Often a Management Error

Rolling back speed may feel safe, but it carries hidden costs:

1️⃣ You destroy the most valuable diagnostic data

Weak points exposed under high load disappear once the system returns to a comfortable state.

2️⃣ You silently accept a false ceiling on system capability

The problem is avoided, not solved.

3️⃣ You guarantee future speed increases will fail again

Because the real bottleneck was never identified or removed.

Rolling back speed relieves pressure on management.

It does nothing to strengthen the system.

Step Four: What to Examine First After a Speed Increase

If the situation points to system mismatch, stop adjusting speed and examine these three foundational variables.

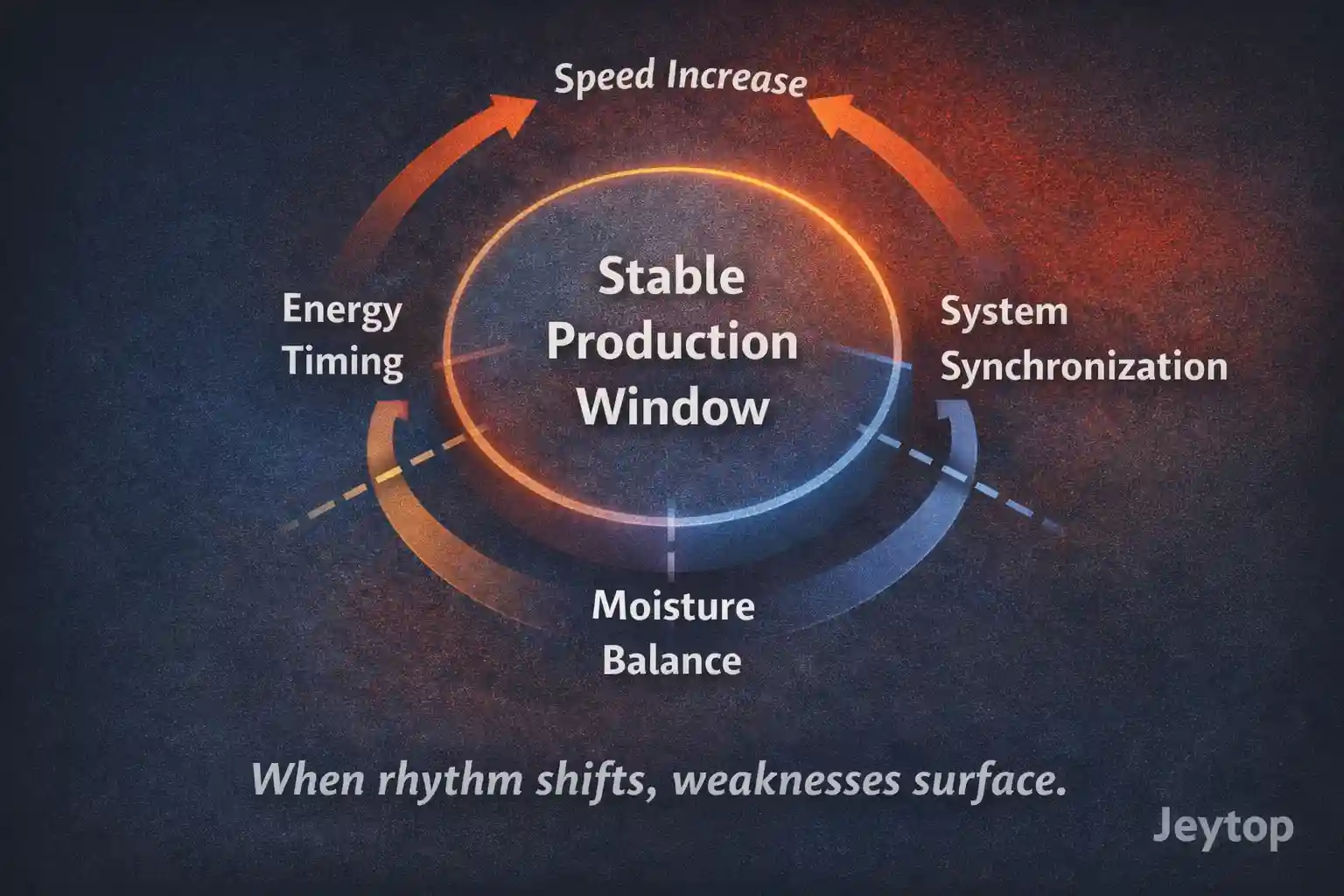

1️⃣ Is Energy Still Delivered at the Right Time?

Higher speed compresses thermal exposure time.

Ask:

- Is heat still penetrating the board structure?

- Is energy driving adhesive gelatinization—or merely evaporating excess moisture?

2️⃣ Is Moisture Accumulating Inside the System?

Higher speed increases water input per unit time—from paper and adhesive.

Ask:

- Can drying and exhaust capacity keep pace?

- Is moisture being carried into downstream processes?

Many failed speed increases are, at their core, moisture migration failures.

3️⃣ Is System Timing Still Synchronized?

From forming to drying to cutting, the line must share a single time reference.

Ask:

- Are drives, motors, and sensors still aligned at millisecond-level precision?

- Are small timing drifts being amplified by higher speed?

At high speed, timing errors grow faster than mechanical ones.

Step Five: Three Instinctive Actions That Must Be Prohibited

Until the diagnosis is clear, avoid these reactions:

❌ Treating speed rollback as the default solution

❌ Panic-driven, isolated parameter adjustments

❌ Forcing operators to “hold it together” by experience alone

All three attempt to silence the system instead of understanding it.

Final Takeaway: Speed Is a System Stress Test

Advanced plants do not fear problems exposed by higher speed.

They fear misinterpreting those problems.

Speed is not the enemy.

The enemy is misunderstanding what the system is telling you.

When quality collapses after a speed increase, exceptional managers do not see a retreat signal.

They see a system capability report—one written in real production data.

Your job is not to make it quiet again.

Your job is to read it correctly.