If you are staring at delamination occurring across the full width of the board while the line is still running at high speed, understand this first:

This is not a routine “parameter adjustment” issue.

It is a clear signal of a system-level failure.

This is not something that can be fixed with local tweaks. At this moment, ideas like “let’s slow down and see” or “add more adhesive” are more likely to increase losses than solve the problem.

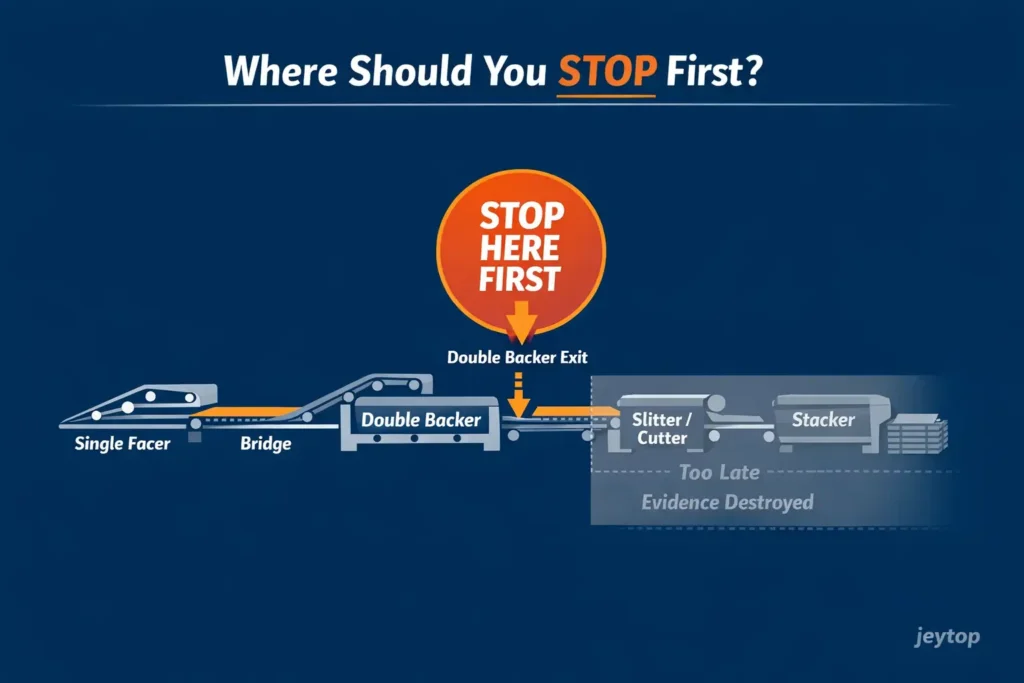

The real question is not whether to stop—but where to stop first.

Stopping at the right point determines whether you control the damage and diagnose effectively.

Stopping at the wrong point destroys the evidence and turns troubleshooting into guesswork.

First, confirm this is truly a “high-speed full-width delamination” event

To avoid misjudgment, make sure all of the following conditions are present. Only then does this article apply:

- Operating condition: The line is running at, or very close to, normal high-speed production.

- Failure scope: Delamination appears across the entire width, or most of the width—not isolated spots or edges.

- Failure behavior: Bond strength collapses rapidly, and on-line “fixes” show little or no effect.

- Accompanying signs: Often accompanied by abnormalities in hot plate temperature, effective bonding time, or other fundamental process conditions.

If the issue only appears at low speed, or is limited to edges or localized areas, you are likely dealing with a different type of problem.For delamination confined to one side or a specific layer, a different diagnostic path applies

But when everything fails at once, the root cause is never a single point—it means the conditions supporting bonding have collapsed system-wide.According to the TAPPI Technical Information Papers index, common corrugator bonding defects and their root causes are documented as system-wide interactions between paper, heat, adhesive, and process conditions. See TAPPI TIP Index for bonding problems.

Why slowing down or adding adhesive is dangerous at this moment

Once full-width delamination has occurred, the system balance is already broken. Blind adjustments usually amplify the damage.

The risk of slowing down

Reducing speed does not restore a failed bonding reaction. It only changes dwell time in the heating zone. In many cases, this converts an obvious, immediate failure into a delayed delamination that appears after stacking—resulting in entire batches being scrapped.This is the same mechanism behind situations where boards appear bonded at the double backer but fail later in downstream handling or at the customer site.

Worse, slowing down often causes you to lose both the failure snapshot and the diagnostic time window.

The adhesive misconception

When heat input or effective bonding time is insufficient, adding adhesive is like pouring fuel onto unlit wood. It does not create bonding—only waste, contamination, and cleanup problems.

In this scenario, the first decision is not how to adjust, but when and where to stop—and that location matters.

First-priority stop point: After the double backer exit, before downstream cutting

This is the single most critical decision in the entire event.

Stopping here serves one purpose: freezing the failure condition.

- Preserve diagnostic clues: The board has just left the bonding and curing zone. Adhesive condition, temperature profile, and moisture distribution remain intact.

- Prevent masking of the failure: Once slitting, cutting, or stacking occurs, mechanical damage destroys the original delamination pattern, making diagnosis far more difficult.

Key action

Execute a line stop and retain several full-width boards that have not entered any downstream processing.

This is not simply stopping production—it is preserving evidence.

Second-priority stop option (if a full line stop is not immediately possible)

If partial continuity must be maintained, do the following without exception:

- Lock current settings: Freeze all parameters on the double backer, heating sections, and related units. No adjustments.

- Physically isolate affected boards: Remove and clearly mark boards with full-width delamination after the cross cutter.

- Establish a shared status: Communicate clearly that the line is in incident diagnostic mode. No experimental changes.

Stop points that must be avoided

- ❌ Stopping only after boards are fully stacked

- ❌ Discovering the issue at the customer site

- ❌ Stopping after multiple rounds of trial adjustments

Remember this:

If you stop only after downstream processes have masked the failure, you have stopped production—but not the incident.

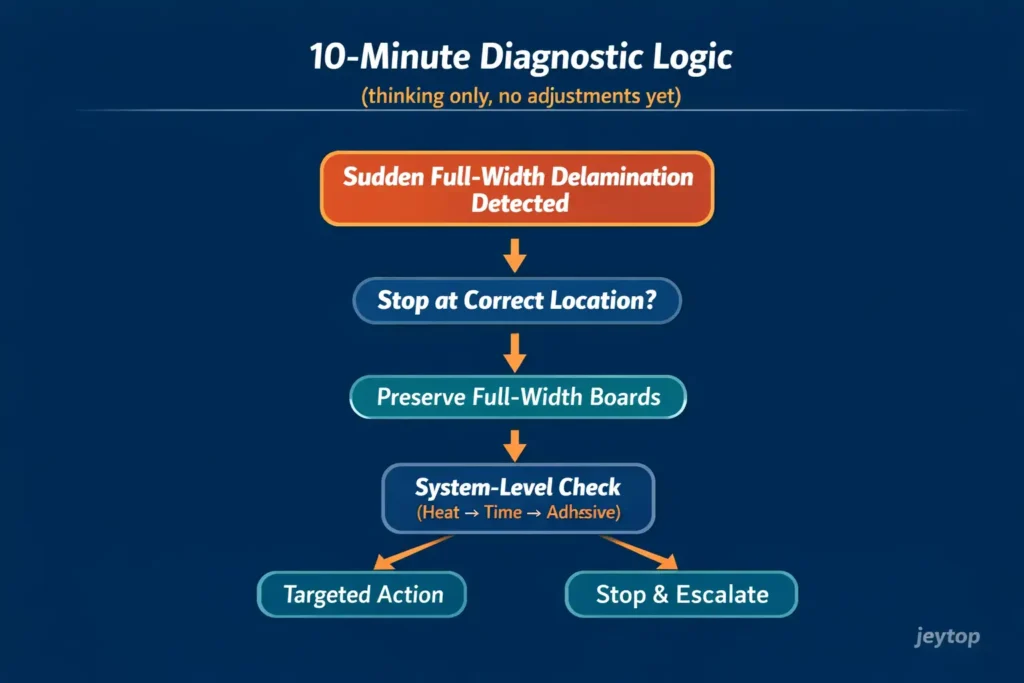

The 10-minute diagnostic logic (thinking only, no adjustments yet)

In full-width delamination cases, failures are rarely sudden. They are usually the result of upstream changes accumulating over time.Similar accumulation effects can also drive sudden one-way warp when physical balance across the board is lost.

Once the line is stable, think through the following sequence—before touching anything:

Step 1: Verify whether heat input has failed system-wide

Quickly confirm whether all heating-related units (hot plates, glue rolls, etc.) are significantly off their target values.

In full-width failures, heat loss or imbalance is always the first suspect.

Step 2: Check whether effective bonding time has been compressed

Is line speed beyond the process window?

Is there slippage or mechanical inconsistency reducing actual heat exposure time?

Step 3: Examine adhesive last

Check for sudden full-width interruptions, valve failures, or severe ratio deviations.

But remember: in full-width delamination, adhesive itself is rarely the primary cause.

This sequence exists to identify system-condition failures—not to find the fastest workaround.

Actions strictly prohibited before the root cause is clear

- ❌ Repeated speed changes “to see if it helps”

- ❌ Adjusting adhesive amount or formulation while running

- ❌ Simultaneous, undocumented changes to multiple parameters

Every “trial” adjustment destroys the baseline condition—the only reliable reference you have for understanding what actually failed.

Final note

Full-width delamination at high speed is not a test of operational skill—it is a test of decision-making.

Mature operations are not defined by never having problems. They are defined by whether, when incident-level signals appear, the team can decisively press pause at the right point.

The real losses are rarely decided at the moment of stopping.

They are decided in the minutes of hesitation, experimentation, and hope that the problem might somehow fix itself.

Your decision in those minutes determines whether this becomes a containable failure—or a long, expensive incident.